LAST DAYS OF THE REBELLION1

By PHILIP H. SHERIDAN.

[Read February 7, 1883.]

PUBLIC attention having of late been occasionally called to some of the events that occurred in the closing scenes of the Virginia campaign, terminating at Appomattox Court House, April 9, 1865, I feel it my duty to give to history the following facts: —

When, April 4, 1865, being at the head of the cavalry, I threw across the line of General Lee’s march at Jettersville, on the Richmond and Danville Railroad, my personal escort, the First United States Cavalry, numbering about two hundred men, a tall, lank man was seen coming down the road from the direction of Amelia Court House, riding a small mule and heading toward Burkesville Junction, to which point General Crook had, early that morning, been ordered with his division of cavalry, to break the railroad and telegraph lines. The man and mule were brought to a halt, and the mule and himself closely examined, under strong remonstrances at the indignity done to a Southern gentleman. Remonstrance, however, was without avail, and in his boots two telegrams were found from the commissary-general of Lee’s army, saying: “The army is at Amelia Court House, short of provisions; send three hundred thousand rations quickly to Burkesville Junction.” One of these despatches was for the Confederate Supply Department at Danville, the other for that at Lynchburg. It was at once presumed that, after the despatches were written, the telegraph line had been broken by General Crook north of Burkesville, and they were on their way to some station beyond the break, to be telegraphed. They revealed where Lee was,

and from them some estimate could also be formed of the number of his troops. Orders were at once given to General Crook to come up the road from Burkesville to Jettersville, and to General Merritt, who, with the other two divisions of cavalry, had followed the road from Petersburg on the south side of and near the Appomattox River, to close in without delay on Jettersville, while the Fifth Army Corps, under the lamented Griffin, which was about ten or fifteen miles behind, was marched at a quick pace to the same point, and the road in front of Lee’s army blocked until the arrival of the remainder of the Army of the Potomac on the afternoon of the next day.

My command was pinched for provisions, and these despatches indicated an opportunity to obtain a supply; so, calling for Lieutenant-Colonel Young, commanding my scouts, four men, in the most approved gray, were selected, — good, brave, smart fellows, knowing every cavalry regiment in the Confederate Army, and as good “Johnnies” as were in that army, so far as bearing and language were concerned. They were directed to go to Burkesville Junction and there separate. Two were to go down the Lynchburg branch of the railroad until a Confederate telegraph station was found, from which they were to transmit by wire the above-mentioned Rebel despatches, represent the suffering condition of Lee’s army, watch for the trains, and hurry the provisions on to Burkesville, or in that direction. The other two were to go on the Danville branch, and had similar instructions. The mission was accomplished by those who went out on the Lynchburg branch, but I am not certain about the success of the other party; at all events, no rations came from Danville that I know of.

I arrived at Jettersville with the advance of my command, the First United States Cavalry, on the afternoon of the 4th of April. I knew the condition and position of the Rebel Army from the despatches referred to, and also from the following letter (erroneously dated April 5),

taken from a colored man who was captured later in the day: —

Amelia C. H., April 5, 1865.

Dear Mamma, —Our army is ruined, I fear. We are all safe as yet. Shyron left us sick. John Taylor is well; saw him yesterday. We are in line of battle this morning. General Robert Lee is in the field near us. My trust is still in the justice of our cause and that of God. General Hill is killed. I saw Murray a few minutes since. Bernard Terry, he said, was taken prisoner, but may get out. I send this by a negro I see passing up the railroad to Michlenburg. Love to all.

Your devoted son,

Wm. B. Taylor,

Colonel.

I accordingly sent out my escort to demonstrate and make as much ado as they could, by continuous firing in front of the enemy at or near Amelia Court House, pending the arrival of the Fifth Corps. That corps came up in the course of the afternoon, and was put into position at right angles with the Richmond and Danville road, with its left resting on a pond or swamp on the left of the road. Toward evening General Crook arrived with his division of cavalry, and later General Merritt, with his two divisions; and all took their designated places. The Fifth Corps, after its arrival, had thrown up earthworks, and made its position strong enough to hold out against any force for the period which would intervene before the arrival of the main body of the Army of the Potomac, now rapidly coming up on the lines over which I had travelled.

On the afternoon and night of the 4th, no attack was made by the enemy upon the small force in his front, — the Fifth Corps and three divisions of cavalry,— and by the morning of the 5th, I began to believe that he would leave the main road if he could, and pass around my left flank to Sailor’s Creek and Farmville. To watch this

suspected movement, early on the morning of the 5th I sent Davies’ brigade of Crook’s division of cavalry to make a reconnoissance in that direction. The result was an encounter, by Davies, with a large train of wagons, under escort, moving in the direction anticipated. The train was attacked by him, and about two hundred wagons were burned, and five pieces of artillery and a large number of prisoners captured. In the afternoon of April 5, the main body of the Army of the Potomac came up. General Meade was unwell, and requested me to put the troops in position, which I did, in line of battle, facing the enemy at Amelia Court House. I thought it best to attack at once, but this was not done. I then began to be afraid the enemy would, in the night, by a march to the right from Amelia Court House, attempt to pass our left flank and again put us in the rear of his retreating columns. Under this impression I sent to General Grant the following despatch: —

Cavalry Headquarters, Jettersville,

April 5, 1865, 3 p. M. Lieutenant-General U. S. Grant,

Commanding Armies of the United States.

General,— I send you the enclosed letter, which will give you an idea of the condition of the enemy and their whereabouts. I sent General Davies’ brigade this morning around on my left flank. He captured at Fames’ Cross-Roads five pieces of artillery, about two hundred wagons, and eight or nine battle-flags and a number of prisoners. The Second Army Corps is now coming up. I wish you were here yourself. I feel confident of capturing the Army of Northern Virginia, if we exert ourselves. I see no escape for Lee. I will put all my cavalry out on our left flank, except Mackenzie, who is now on the right.

(Signed) P. H. Sheridan,

Major- General.

On receipt of this, General Grant immediately started for my headquarters at Jettersville, arriving there about

eleven o’clock of the night of April 5. Next morning, April 6, the infantry of the army advanced on Amelia Court House. It was found before reaching it that the enemy had turned our left flank and taken another road to Sailor’s Creek and Farmville. The cavalry did not advance with the infantry on Amelia Court House, but moved to the left and rear at daylight on the morning of the 6th, and struck the moving columns of the enemy’s infantry and artillery, with which a series of contests ensued that resulted in the battle of Sailor’s Creek, where Lieutenant-General Ewell lost his command of about ten thousand men, and was himself taken prisoner, together with ten other general officers.

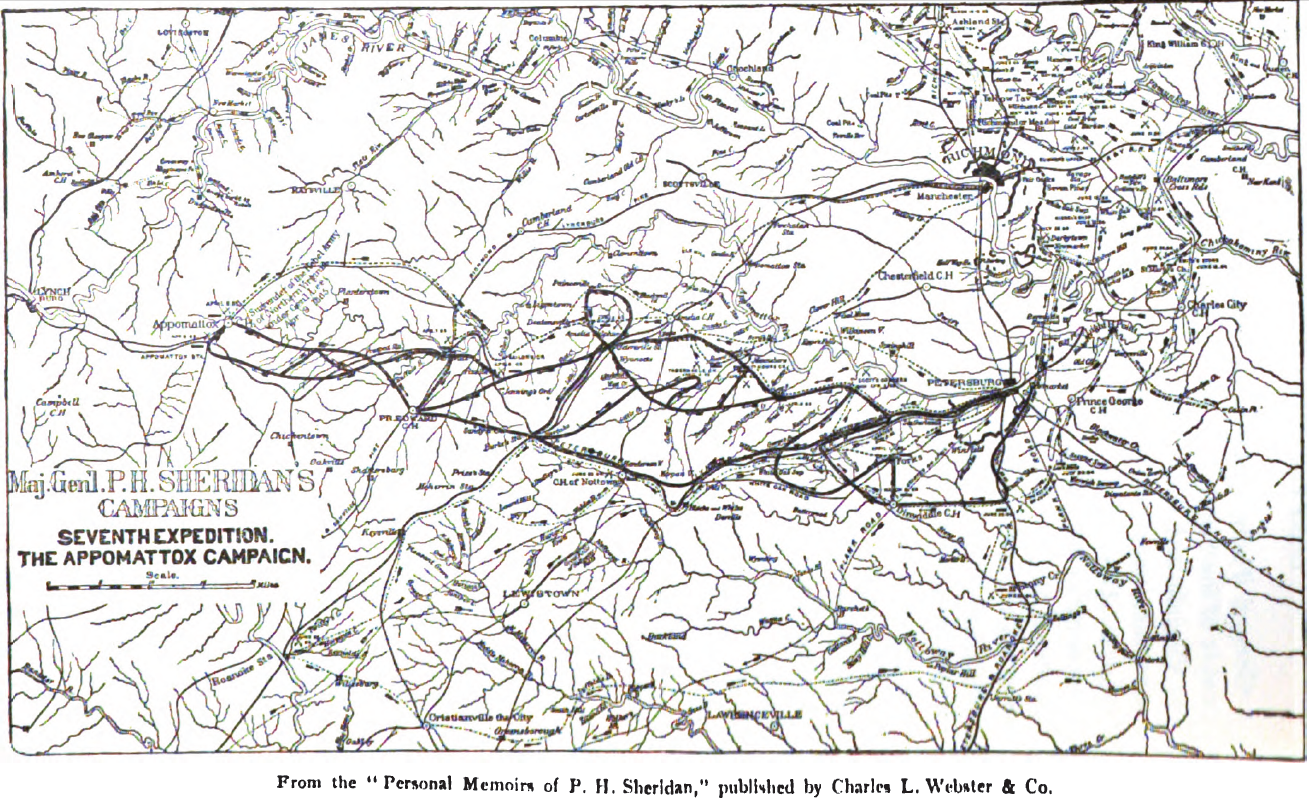

We now come to the morning of the 7th. I thought that Lee would not abandon the direct road to Danville through Prince Edward’s Court House, and early on the morning of the 7th directed General Crook to follow up his rear, while with Merritt (Custer’s and Devens’ divisions) I swung off to the left, and moved quickly to strike the Danville road six or eight miles south of Prince Edward’s Court House, and thus again head or cut off all or some of the retreating Confederate Army. On reaching that road, it was found that General Lee’s army had not passed, and my command was instantly turned north for Prince Edward’s Court House. A detachment ordered to move with the greatest celerity, via Prince Edward’s Court House, reported that Lee had crossed the Appomattox at and near Farmville, and that Crook had followed him. On looking at the map it will be seen that General Lee would be obliged to pass through Appomattox Court House and Appomattox station on the railroad, to reach Lynchburg by the road he had taken north of the Appomattox River, and that that was the longest road to get there. He had given the shortest one—the one south of the river—to the cavalry. General Crook was at once sent for, and the three divisions, numbering perhaps at that time seven thousand men,

concentrated on the night of the 7th of April at and near Prospect station on the Lynchburg and Richmond Railroad, and Appomattox station became the objective point of the cavalry for the operations of the next day, the 8th. Meantime my scouts had not been idle, but had followed down the railroad, looking out for the trains with the three hundred thousand rations which they had telegraphed for on the night of the 4th. Just before reaching Appomattox station, they found five trains of cars feeling their way along in the direction of Burkesville Junction, not knowing exactly where Lee was. They induced the person in charge to come farther on, by their description of the pitiable condition of the Confederate troops. Our start on the morning of the 8th was before the sun was up; and having proceeded but a few miles, Major White, of the scouts, reached me with the news that the trains were east of Appomattox station, that he had succeeded in bringing them on some distance, but was afraid that they would again be run back to the station. Intelligence of this fact was immediately communicated to Crook, Merritt, and Custer, and the latter, who had the advance, was urged not to let the trains escape, and I pushed on and joined him. Before reaching the station, Custer detailed two regiments to make a detour, strike the railroad beyond the station, tear up the track, and secure the trains. This was accomplished, but on the arrival of the main body of our advance at the station it was found that the advance-guard of Lee’s army was just coming on the ground. A sanguinary engagement at once ensued. The enemy was driven off, forty pieces of artillery captured, and four hundred baggage-wagons burned. The railroad trains had been secured in the first onset, and were taken possession of by locomotive engineers, soldiers in the command, whose delight at again getting at their former employment was so great that they produced the wildest confusion by running the trains to and fro on the track, and making such an unearthly screeching with

the whistles that I was at one time on the point of ordering the trains burned; but we finally got them off, and ran them to our rear ten or fifteen miles, to Ord and Gibbon, who with the infantry were following the cavalry. The cavalry continued the fighting nearly all that night, driving the enemy back to the vicinity of Appomattox Court House, a distance of about four miles, thus giving him no repose, and covering the weakness of the attacking force.

I remember well the little frame house just south of the station where the headquarters of the cavalry rested, or rather remained, for there was no rest on the night of the 8th. Despatches were going back to our honored chief, General Grant, and Ord was requested to push on the wearied infantry. To-morrow was, in all reasonable probability, to end our troubles; but it was thought necessary that the infantry should arrive, in order to doubly insure the result. Merritt, Crook, and Custer were at times there. Happiness was in every heart. Our long and weary labors were about to close, our dangers soon to end. There was no sleep; there had been but little for the previous eight or nine days. Before sunrise General Ord came in, reporting the near approach of his command. After a hasty consultation about positions to be taken up by the incoming troops, we were in the saddle and off for the front, in the vicinity of Appomattox Court House. As we were approaching the village, a heavy line of Confederate infantry was seen advancing, and rapid firing commenced. Riding to a slight elevation, where I could get a view of the advancing enemy, I immediately sent directions to General Merritt for Custer’s and Devens’ divisions to fall back slowly, and as they did so, to withdraw to our right flank, thus unmasking Ord’s and Gibbon’s infantry. Crook and Mackenzie, on the extreme left, were ordered to hold fast. I then hastily galloped back to give General Ord the benefit of my information. No sooner had the enemy’s line of battle

reached the elevation from which my reconnoissance had been made, and from whence could be distinctly seen Ord’s troops in the distance, than he called a sudden halt, and a retrograde movement began to a ridge about one mile to his rear. Shortly afterward I returned from General Ord to the front, making for General Merritt’s battle-flag on the right flank of the line. On reaching it, the order to advance was given, and every guidon was bent to the front; and as we swept by toward the left of the enemy’s line of battle, he opened a heavy fire from artillery. No heed was paid to the deadly missiles, and with the wildest yells, we soon reached a point some distance to his right and nearly opposite Appomattox Court House. Beyond us, in a low valley, lay Lee and the remnant of his army. There did not appear to be much organization, except in the advanced troops under General Gordon, whom we had been fighting, and a rearguard under General Longstreet, still farther up the valley. Formations were immediately commenced, to make a bold and sweeping charge down the grassy slope; when an aide-de-camp from Custer, filled with excitement, hat in hand, dashed up to me with the message of his chief: ” Lee has surrendered; don’t charge; the white flag is up!” Orders were given to complete the formation, but not to charge.

Looking to the left, to Appomattox Court House, a large group was seen near the lines of Confederate troops that had fallen back to that point. General Custer had not come back, and supposing that he was with the group at the Court House, I moved on a gallop down the narrow ridge, followed by my staff. The Court House was, perhaps, three fourths of a mile distant. We had not gone far before a heavy fire was opened on us from a skirt of timber to our right, and distant not much over three hundred yards. I halted for a moment, and taking off my hat, called out that the flag was being violated, but could not stop the firing, which now caused us all to take shelter

in a ravine running parallel to the ridge we were on, and down which we then travelled. As we approached the Court House, a gentle ascent had to be made. I was in advance, followed by a sergeant carrying my battle-flag. Within one hundred to one hundred and fifty yards from the Court House and the Confederate lines, some of the men in their ranks brought down their guns to an aim on us, and great effort was made by their officers to keep them from firing. I halted, and hearing some noise behind, turned in the saddle, and saw a Confederate soldier attempting to take my battle-flag from the color-bearer. This the sergeant had no idea of submitting to, and had drawn his sabre to cut the man down. A word from me caused him to return his sabre, and take the flag back to the staff-officers, who were some little distance behind. I remained stationary a moment after these events, then calling a staff-officer, directed him to go over to the group of Confederate officers, and demand what such conduct meant. Kind apologies were made, and we advanced. The superior officers met were General J. B. Gordon and General Cadmus M. Wilcox, the latter an old army officer. As soon as the first greeting was over, a furious firing commenced in front of our own cavalry, from whom we had only a few minutes before separated. General Gordon seemed to be somewhat disconcerted by it. I remarked to him : ” General Gordon, your men fired on me as I was coming over here, and undoubtedly they have done the same to Merritt’s and Custer’s commands. We might just as well let them fight it out.” To this proposition General Gordon did not accede. I then asked, ” Why not send a staff-officer, and have your people cease firing? They are violating the flag. ” He said, ” I have no staff-officer to send.” I replied, ” I will let you have one of mine,” and calling for Lieutenant Vanderbilt Allen, he was directed to report to General Gordon and carry his orders. The orders were to go to General Geary, who was in command of a small brigade of South Carolina

cavalry, and ask him to discontinue the firing. Lieutenant Allen dashed off with the message; but, on delivering it to General Geary, was taken prisoner, with the remark from that officer that he did not care for white flags, that South Carolinians never surrendered.

It was about this time that Merritt, getting impatient at the supposed treacherous firing, ordered a charge of a portion of his command. While General Gordon and Wilcox were engaged in conversation with me, a cloud of dust, a wild hurrah, a flashing of sabres, indicated a charge; and the ejaculations of my staff-officers were heard: ” Look! Merritt has ordered a charge.” The flight of Geary’s brigade followed ; Lieutenant Allen was thus released. The last gun had been fired, and the last charge made in the Virginia campaign.

While the scenes thus related were taking place, the conversation I now speak of was occurring between General Gordon and myself. After the first salutation, General Gordon remarked: ” General Lee asks for a suspension of hostilities pending the negotiations which he has been having for the last day and night with General Grant.” I rejoined: “I have been constantly informed of the progress of the negotiations, and think it singular that while such negotiations are going on, General Lee should have continued his march and attempted to break through my lines this morning with the view of escaping. I can entertain no terms except the condition that General Lee will surrender to General Grant on his arrival here. I have sent for him. If these terms are not accepted, we will renew hostilities.” General Gordon replied: ” General Lee’s army is exhausted. There is no doubt of his surrender to General Grant on his arrival.”

General Wilcox, whom I knew quite well, he having been captain of the company to which I was attached as a cadet at the military academy, then stepped to his horse, and taking hold of the saddle-bags, said in jocular way: “Here, Sheridan, take these saddle-bags; they

have one soiled shirt and a pair of drawers. You have burned everything else I had in the world, and I think you are entitled to these also.” He was alluding, of course, to the destruction of the baggage trains which had been going on for some days.

When the terms above referred to were settled, each army agreed to remain in statu quo until the arrival of General Grant, whom Colonel Newhall, my adjutant-general, had gone for. Generals Gordon and Wilcox then returned to see General Lee, and promised to come back in about thirty minutes, and during that time General Ord joined me at the Court House. At the end of thirty or forty minutes, General Gordon returned in company with General Longstreet. The latter, who commanded Lee’s rear-guard back on the Farmville road, seemed somewhat alarmed lest General Meade, who was following up from Farmville, might attack, not knowing the condition of affairs at the front. To prevent this, I proposed to send my chief of staff, General J. W. Forsyth, accompanied by a Confederate officer, back through the Confederate Army, and inform General Meade of the existing state of affairs. He at once started, accompanied by Colonel Fairfax, of General Longstreet’s staff, met the advance of the Army of the Potomac, and communicated the conditions.

In the mean time, General Lee came over to McLean’s house, in the village of Appomattox Court House. I am not certain whether General Babcock, of General Grant’s staff, who had arrived in advance of the General, had gone over to see him or not. We had waited some hours, and, I think, about twelve or one o’clock General Grant arrived. General Ord, myself, and many officers were in the main road leading through the town, at a point where Lee’s army was visible. General Grant rode up, and greeting me with, “Sheridan, how are you?” I replied, ” I am very well, thank you.” He then said, ” Where is Lee ? “I replied, ” There is his army down in that valley; he is over in that house,” pointing out McLean’s, “waiting

to surrender to you.” General Grant, still without dismounting, said, “Come, let us go over.” He then made the same request of General Ord, and we all went to McLean’s house. Those who entered with General Grant were, as nearly as I can recollect, Ord, Rawlins, Seth Williams, Ingalls, Babcock, Parker, and myself; the staff-officers, or those who accompanied, remaining outside on the porch steps and in the yard. On entering the parlor, we found General Lee standing in company with Colonel Marshall, his aide-de-camp. The first greeting was to General Seth Williams, who had been Lee’s adjutant when he was superintendent of the military academy. General Lee was then presented to General Grant, and all present were introduced. General Lee was dressed in a new gray uniform, evidently put on for the occasion, and wore a handsome sword. He had on his face the expression of relief from a heavy burden. General Grant’s uniform was soiled with mud and service, and he wore no sword. After a few words had been spoken by those who knew General Lee, all the officers retired, except, perhaps, one staff-officer of General Grant and the one who was with General Lee. We had not been absent from the room longer than about five minutes, when General Babcock came to the door, and said, “The surrender has taken place; you can come in again.”

When we re-entered, General Grant was writing on a little wooden elliptical-shaped table (purchased by me from Mr. McLean and presented to Mrs. G. A. Custer) the conditions of the surrender. General Lee was sitting, his hands resting on the hilt of his sword, at the left of General Grant, with his back to a small marble-topped table, on which many books were piled. While General Grant was writing, friendly conversation was engaged in by General Lee and his aid with the officers present, and he took from his breast-pocket two despatches, which had been sent to him by me during the forenoon, notifying him that some of his cavalry in front of Crook were vio-

lating the agreement entered into by withdrawing. I had not had time to make copies when they were sent, and had made a request to have them returned. He handed them to me with the remark, “I am sorry. It is possible my cavalry at that point of the line did not fully understand the agreement.”

About one hour was occupied in drawing up and signing the terms, when General Lee retired from the house with a cordial shake of the hand with General Grant, mounted his chunky gray horse, and lifting his hat, passed through the gate, and rode over the crest of the hill to his army. On his arrival there, we heard wild cheering, which seemed to be taken up progressively by his troops, either for him, or because of satisfaction with his last official act as a soldier.

Source:

- Military Essays and Recollections. Papers Read before the Commandery of the State of Illinois, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Volume 1, pages 426-439 ↩