VIII

THE FAILURE TO TAKE PETERSBURG ON JUNE 16-18, 18641

BY

JOHN C. ROPES, ESQ.

Read before the Society February 17, 1879

THE FAILURE TO TAKE PETERSBURG ON JUNE 16-18,1864

The fifteenth of Jane, 1864, had been a successful day for the Union Army. General W. F. (Baldy) Smith, with the 18th Corps, had attacked and carried works of great strength in front of Petersburg. He had captured fifteen guns and three hundred prisoners.

Two divisions of General Hancock’s Corps, the Second, had, at General Smith’s request, relieved the 18th Corps in the works he had carried, and had, by eleven o’clock at night, occupied the works “from the Friend house on the right to the Dunn house on the left of the Prince George Road.”(1) And although Hancock goes on to say that it was then “too late and dark for an immediate advance,” yet he did at midnight instruct “Generals Birney and Gibbon, that, if any commanding points were held by the enemy between their positions and the Appomattox, they should be attacked and taken at or before daylight.”(2) “I was extremely anxious,” he goes on to say, “that all the ground between my line and the river should be in our possession before the enemy could get his heavy reinforcements up. These instructions were not promptly complied with, and it was not till about 6 A. M. on the 16th that Generals Birney and Gibbon advanced to reconnoitre the ground in their front, by which time the enemy had moved a considerable body of fresh troops on the field, had occupied the large redoubt and rifle-pits in front of the Avery house, and had greatly strengthened their positions at all important points.”

While the censure passed by General Hancock upon his

***

(1) 80 W. R. 305.

(2) The italics are mine. See the order, in 80 W. R. 317.

***

division commanders must remain, it is quite possible that the delay of three hours had not made any appreciable difference in the force of the enemy. Hagood’s Brigade of Hoke’s Division was up, we know, early in the evening before, and there is good reason to believe that Martin’s Brigade was also up before the attack by the 18th Corps was over. It is not probable that the Second and Third Brigades were far behind their comrades. It is, however, certain that no other reenforcements had arrived. Very possibly, an attack “at or before daylight” might have found the arrangements of the enemy incomplete, might have taken them by surprise even; and, of course, it ought to have been made. But we are inclined to believe that it would have been resisted by precisely the same troops whom Hancock refers to as having been noticed at six o’clock A. M., and by no fewer or other troops. It must be remembered also that by six o’clock A. M. Barlow’s Division had arrived, so that Hancock had his whole corps with him, numbering about 21,000 officers and men, together with the 18th Corps, numbering perhaps 10,000 more. Against this force, — and it was a very formidable force, for there was no corps that stood higher than the 2d, and the 18th was elated by victory, — were only Hoke’s Division, Wise’s Brigade, and Dearing’s Cavalry, in all about 8000 men. Had Hancock known this, he could doubtless have driven them from all their lines before Johnson came up. But he attempted nothing of the sort. The Confederate troops stoutly resisted the reconnoissance, and gave our people the impression that they were in very considerable force, and that we had better be careful. This policy on the part of the enemy, of which we shall see more instances as we proceed, was extremely wise, for it not only induced our commanders to delay assaulting their works, but deterred them from detaching any force to their left to turn the works by way of the Jerusalem Plank Road. Thus on this morning another opportunity was lost by us.

When the enemy fell back on the night of the 15th they abandoned all the redoubts and connecting works numbered from 4 or 5 to 14, inclusive. They did not, so far I as can ascertain, retire to any regularly laid-out line of defence, but dug rifle-pits, and threw up slight works, a short distance in rear of the captured works. The new line, such as it was, ran in a general way from northwest to southeast. Starting from their battery, No. 3, on their left, a line of slight works running in this general direction, and covering the hill on which the Hare house stood, entered the thick woods through which Harrison’s Creek flows. For a mile or so there seems to be no trace of any line, but further to the southeast, and directly in rear of Battery 14 and three quarters of a mile from it, we find a line of pits, the southern end of which must have been somehow connected with the redoubt just east of the Shand house and with the works adjacent thereto. This redoubt was either the one of their original works which was numbered 15, or was close to it. There appears to have been no line south of this redoubt.

At ten o’clock A. M. of the 16th three brigades of Bushrod Johnson’s Division arrived from Bermuda Hundred, increasing the enemy’s force to at least 14,000 men. (See note A at the close of this paper.) They were placed on the right of Hoke’s Division, occupying the Shand house, and probably extending their line still further to the southward.

At the same time the Federal Army also received reenforcements. The 9th Corps, which on the evening before Grant had ordered up, began to arrive, having crossed at the upper pontoon bridge above Fort Powhatan, and having marched all night. The rest of the day was spent in getting the troops, who were tired, hot, and dusty, after their long march, into their position on the left of the 2d Corps.

During the forenoon the Lieutenant-General arrived, and ordered Hancock to reconnoitre in preparation for an attack to be made that afternoon. This reconnoissance, which was

smartly disputed by the enemy, was made by General Birney on the left of the Prince George Road and in front of the hill on which the Hare house stood. General Meade came up at a quarter before two o’clock in the afternoon.

Every effort seems to have been made to select the best place for the proposed attack. General Humphreys, the Chief of Staff, and General Barlow, made a close reconnoissance, and came very near being shot. The skirmishing was very heavy along our whole line. Beauregard, as has been already pointed out, fully recognized the necessity of magnifying his numbers, and his division commanders fought their troops admirably, showing great persistence and skill. Our losses were quite heavy. Doubtless the enemy lost severely, too.

At six o’clock P. M. our batteries opened heavily upon the enemy’s lines, chiefly from the captured works, which were on a commanding rise of ground. General Meade rode out into the open to see all that could be seen, and to be ready for any emergency. Here he was under fire, and came very near being killed by a round shot. Then the infantry was put in.

Barlow’s Division on the left, Birney’s in the centre, and a part of Gibbon’s on the right, dashed into the woods which concealed the enemy’s lines in front, and to the left of the Hare house. The 2d Corps was supported by two brigades of the 9th Corps and two of the 18th Corps, but these troops were not actively engaged, though Griffin’s Brigade of the 9th Corps was under artillery fire. “The advance,” says General Hancock, in his report,(1) was ” spirited and forcible, and resulted after a fierce conflict, in which our troops suffered heavily, in driving the enemy back some distance along our whole line. The severe fighting ceased at dark, although the enemy made several vigorous attempts during the night to retake the ground which he had lost. In this, however, he was foiled, as our troops had intrenched themselves at dark,

***

(1) 80 W. R. 306.

***

and repelled all efforts to dislodge them.” Captain McCabe, in his Defence of Petersburg (2 So. Hist. Soc. Papers, 268), says: “For three hours the fight raged furiously along the whole line with varying success, nor did the contest subside until after nine o’clock, when it was found that Birney, of Hancock’s Corps, had effected a serious lodgment, from which the Confederates in vain attempted to expel him during the night.” I am inclined to believe that the “lodgment” spoken of was made by Barlow, and not by Birney. Gibbon’s Division was not severely engaged. The corps lost about 2500 men.

It would doubtless have been better if the attack had been made farther to our left. By remaining in the Shand house redoubt the enemy had most unwisely exposed himself. This part of his works, which was part of his original line and was fully manned, as we shall soon see, was a half a mile or so out in front of his line of rifle-pits. Of this, advantage was, however, taken in the morning of the 17th.

In the evening of the 16th, and during the ensuing night, the 5th Corps, under General Warren, and the 2d Division of the 6th Corps, under General Neill, arrived. Neill’s Division relieved that of Brooks of the 18th Corps, which was sent at once to Bermuda Hundred. The corps of Warren was placed on the left of the 9th Corps.

As for the other two divisions of the 6th Corps they had been sent under Wright to Bermuda Hundred, where they arrived on the morning of the 17th. We shall speak of them further on.

General Meade had now with him in front of Petersburg two divisions of Smith’s 18th Corps under Martindale and Hincks; one division of the 6th Corps under Neill; three divisions of Hancock’s 2d Corps under Gibbon, Birney, and Barlow; three divisions of Burnside’s 9th Corps under Ledlie, Willcox, and Potter (for Ferrero’s Division was still in rear with the trains) ; four divisions of Warren’s 5th Corps under

Griffin, Ayres, Crawford, and Cutler; in all thirteen divisions, say, 80,000 to 90,000 men. These troops were in good condition, too. They were not, it is true, fond of attacking field works, but as matter of fact they did attack them with spirit and determination. They were certainly perfectly able to fight an ordinary battle. For all the common experiences of war, the Army of the Potomac was in good fighting trim. This is the almost unanimous testimony of the officers with whom I have talked.

Meade had with him, however, so far as I can discover, only the cavalry of Kautz. Wilson’s Cavalry, he says in his report,(1) was guarding the trains. Sheridan was, during this whole movement, on one of those useless raids which General Grant seems to have greatly favored. Had he accompanied the army to Petersburg, it is not too much to say that the defenceless state of the enemy’s southern line would have been promptly ascertained, and Petersburg captured.

How was it with the enemy? Incredible as it may sound, they had received no reinforcements since the arrival of Johnson’s Division. These two divisions of Hoke and Johnson, — the brigade of Gracie was not sent over from Bermuda Hundred till the evening of the 17th, — with perhaps a thousand men of Dealing’s Cavalry, say 14,000 men in all, undertook this 17th of June to defend Petersburg against 80,000 men. We cheerfully recognize in the enemy’s troops all the great soldierly qualities; courage, tenacity, mastery of all the resources of their position, confidence in themselves; to their commanders, Beauregard, Hoke, Bushrod Johnson, must be awarded not only great tactical skill, but a clear comprehension of the true role for them to play, and the courage to play it. Few as their numbers were, the enemy always undertook to recapture every position from which we had driven them. “The enemy,” says Hancock,(2) speaking of the positions won by us in the evening of the 16th, “made several vigorous

***

(1) 80 W. R. 168.

(2) Ibid. 306.

***

attempts to retake the ground which he had lost. In this, however, he was foiled, as our troops had intrenched themselves at dark, and repelled all efforts to dislodge them.” So on the 17th:(1) “The enemy made frequent efforts to retake the Hare house during the day, but were handsomely repelled on each occasion.” To the same effect speaks General Burnside, regarding the attack on the evening of the 17th:(2) “The line was carried and held till ten o’clock at night, when ‘our’ advance was driven in by an overpowering force of the enemy.” This apparently wasteful use of the very small number of men in his command was in reality the wisest thing Beauregard could do. Who of the Federal generals could suppose that this ever active, pertinacious enemy, as willing to assault breastworks as any troops in the Army of the Potomac, numbered in reality about one sixth of our own forces ? It must have appeared almost certain to our generals that the Confederates must have had a large force in their lines, or they never would have squandered so many lives in vain attempts to recapture the positions from which they had been driven. Hence General Meade did not dare to extend his left, for fear of weakening his right. Had he known the actual state of affairs, he could have left Smith, Neill, and Hancock in front of the enemy’s works, and could have turned their whole line, by way of the Jerusalem Plank Road, with the 5th and 9th Corps. Beauregard, in a letter(3) addressed to General Wilcox, says: “About four and a half miles of the fortified lines (extending from half a mile east of the Jerusalem Plank Road and westwardly to the Appomattox) were entirely unprotected, except by a few pickets of cavalry, stationed there to give me timely notice of any danger threatening in that direction. It is evident that, if the enemy had left one corps in my front, and attacked with another corps by the Jerusalem Plank Road, or westwardly of it, I would have been compelled to evacuate Petersburg without much resistance.

***

***

But they persisted in attacking on my front, where I was strongest.”

On the morning of the 17th the advantage of position was entirely with the Federal Army. Opposite its right centre was the Hare house, on a somewhat commanding hill, and it was evident that the success of the evening before rendered its capture no difficult matter. This would of course be a break in the enemy’s line. It was also plain that the enemy’s position near the Shand house, far on our left, was entirely untenable, and that not only could an important capture be made there, but, what was of vastly more importance, the whole line could be forced. To these tasks the 2d and 9th Corps were abundantly adequate. There remained the 5th Corps, which could be moved on our left flank by way of the Jerusalem Goad, to turn the enemy’s position completely. Then the two divisions of the 18th Corps and Neill’s Division of the 6th Corps were present, and also could be made use of as occasion might require. There was this day a good chance of winning a great victory. It was almost our last chance, too, for the Army of Northern Virginia arrived at half-past eight the next morning.

Everybody knows that this chance was lost. Whether it was owing to the very difficult nature of the country, to the absence of the cavalry, to a want of enterprise and energy on the part of some commanders, and of military skill on the part of others, — at any rate, the chance was lost. The two obvious things were done, of course, — the Hare house hill and the Shand house redoubt were captured, but that was all. Four guns and seven or eight hundred prisoners were taken, to be sure, but what was that with such an opportunity before us?

However, this 17th day of June was a day of hard fighting, and the operations in themselves are interesting.

On our right centre, Birney and Gibbon, after a brief and easy contest, drove the enemy from the hill on which the Hare house stood, and occupied it. “The enemy made,”

says Hancock,(1) “frequent attempts to retake the Hare house during the day, but were handsomely repulsed.”

It would seem by the map that this capture of the Hare house hill must have rendered all the lines to the southward of it untenable. How the enemy managed to retain their positions on their centre and right after its capture, it is hard to see. It can only be explained by the supposition that there was no unity in the attacks made by the wings of our army, — a supposition for which there is in fact too much evidence. So far as one can judge, there were no works of any kind running from west to east; and, after the capture of the Hare House hill, what was there to prevent our troops from marching southward, covered from the fire from the high ground on Cemetery Hill by the great ridge, and taking in reverse the lines which were afterwards attacked by the 9th Corps ?

The operations of the 9th Corps were begun by the assault on the Shand house redoubt by General Potter’s Division.

The 3d Brigade of Bushrod Johnson’s Division, composed of five Tennessee regiments, held this redoubt, which was located a short distance southeastwardly of the Shand house. The enemy’s line ran from the redoubt northwestwardly, covering the Shand house, and was protected by a ravine, through which ran a small brook. General Potter says : “On reconnoitring the ground in my front, I found it full of gullies and small ravines, which would delay an advance, and I resolved to take advantage of these inequalities to get as near the enemy’s position as possible. We were greatly delayed by the exhaustion of the troops, who had been under arms, and on the march, since 1 P. M. of the 15th, and had marched all night; the moment a regiment was halted the men would drop down asleep, and it was with great difficulty they could be aroused. However, Griffin and Curtin [commanding the two brigades] finally got their brigades massed close up to the enemy’s line. The enemy were inside of their intrench-

***

***

ments, and had not put out any pickets since they were driven in by the attack in the afternoon; they gave us an occasional shot, but I think had no idea of our proximity.” “So near was that position to the Rebels,” says the historian of the 6th New Hampshire, “that all orders had to be given in whispers. The leading regiments were ordered to observe the strictest silence, and to advance without firing a shot, carrying the works at the point of the bayonet. Canteens were placed in haversacks to avoid their rattling, and a death-like stillness pervaded the line. Just as the dawning day began to lighten the eastern horizon the order was given to advance. The men sprang to their feet, and moving quickly and noiselessly upon the Rebel lines, took the enemy completely by surprise, capturing or putting to flight the whole force, and sweeping their line for a mile in extent. By this adroit movement nearly one thousand prisoners fell into our hands, besides four pieces of artillery, caissons and horses, more than a thousand stand of small arms, and a quantity of ammunition.” General Potter had his horse shot under him.

General Burnside in his report says(1) that all the lines and redoubts of the enemy on the ridge on which stood the Shand house were taken; he places the number of the prisoners at 600, and says five colors were taken. Of these the 9th New Hampshire captured one, that of the 23d Tennessee.(2)

Taken by itself, nothing could have been better managed than this affair. But it ought to have secured more important results than the capture of a few cannon, flags, and prisoners, and it was intended originally that it should. General Potter tells us that it was understood that “General Barlow would attack simultaneously.” He further says that his division was

***

(1) 80 W. R. 522.

(2) In Adjutant General’s Report, 1866, vol. ii, p. 695, it is stated as the 53d Tennessee. But the 53d Tennessee was not in Johnson’s Division. The 63d and 23d were in his 3d Brigade: see 3 So. Hist. Soc. Roster, 120, ad finem libri. The 63d was apparently transferred to Gracie’s Brigade; see McCabe’s letter to J. C. R. (Unp. Rep. M. H. S. M., p. 211).

***

to be supported by that of General Ledlie. “After getting my division into position,” he goes on to say, “I found that Barlow had given up all idea of making the attack,” and, “on reporting this, I was informed that I was to get ready for the attack without reference to any one else, although Barlow would doubtless be ordered to unite in time.” He afterwards says that, just before he made the attack, he sent to find out the condition of his support and cooperating division; “report was brought back that they were all asleep, had abandoned all idea of an attack being made, and that it would take some time to get them ready. The short night was rapidly wearing away; it seemed hardly possible to withdraw before daylight, and my advanced position rendered such a move extremely dangerous. I therefore ordered the attack.” It is hard to understand why this state of things should exist. One would suppose that there would have been no insuperable difficulty in seeing to it that the divisions which were to support a carefully planned assault like this should not “abandon the idea” and go quietly to sleep; but it seems to have been beyond the power of the military authorities to prevent these divisions from exercising their freedom of choice in this matter. General Burnside in his report says:(1) “There was considerable delay in getting up the troops of the First Division, owing to the obstacles which intervened between this division and General Potter’s, the whole ground being covered by fallen timber over which it was very difficult to pass in the dark.” The fact is, nobody thought of this beforehand. Had the supporting part of the programme been prepared as carefully as the attacking part, it could, no doubt, have been as successfully carried out. But this is exactly where, for some reason or other, our military machinery always gives out. Pickett at Gettysburg; Upton, and afterwards Barlow, at Spottsylvania; Barlow at Cold Harbor; the Third, and afterwards the First, Divisions of the 9th Corps at

***

(1) 80 W. R. 522.

***

the Shand house ; Gordon at Fort Steadman; it is always the same story; a gallant attack, and no supports in readiness.

Let us see what would have been gained, if they had been forthcoming. Burnside limits himself to saying(1) that “the victory would probably have been very much more decisive.” Potter says: “Had Barlow’s and Ledlie’s Divisions joined, I think we should have had the whole of the line from the Appomattox to the Jerusalem Plank Road, almost without opposition.” Griffin, for it may be supposed to be Griffin who writes in the Adjutant General’s report the narrative of his old regiment, the 6th New Hampshire, says: “A wide breach was made in the enemy’s lines, and there was nothing to prevent an advance into the city, had supports come up in time.”

The resemblance between this affair and that at Spottsylvania on the twelfth of May cannot fail to strike every one. In both cases the enemy paid the penalty for occupying a salient from their main line. In both cases the tactical dispositions were carefully made, and the assaults were perfectly successful. In both cases the supporting operations showed that but little thought had been bestowed upon them, and that there was not military skill enough at hand to supply this deficiency.

After their defeat the enemy retired to “a new and very strong position,” and General Potter pushed his pickets close up to their line.(2)

During the morning, Willcox’s Division (the Third) of the 9th Corps, in conjunction with Barlow’s of the 2d, attacked the position in front of Potter, but, notwithstanding the gallantry of Hartranft and Christ, nothing was gained, and the loss was very severe. Our troops suffered especially from an enfilading fire of artillery from our left.

The Second and Third Divisions of the 9th Corps having tried, one after the other, what they could do, the First was now put in at four o’clock in the afternoon. It was to make the

***

(1) 80 W. R. 522.

(2) Ibid. 522.

***

attack at about the same place where Willcox had attacked in the forenoon, and it was to make it, as usual, entirely without supports. Yet not only was the Second Division (Potter’s) probably available for this purpose, for its losses in the morning had been small, but there was at General Meade’s disposal the whole 5th Corps. Yet not the smallest provision for supporting this attack seems to have been made.

Colonel Gould, of the 59th Massachusetts, took command of the division, as General Ledlie preferred not to expose his precious life. Colonel Weld, of the 56th Massachusetts, commanded the First Brigade, which, with the Second Brigade, constituted the first line, the Third Brigade being the second line. After an hour or more spent in lying in a ravine, awaiting the order, and exposed to artillery fire all the time, the order to charge was given about six o’clock, and the troops in excellent order and with dashing courage crossed with a rush, and without firing a shot, the two hundred yards separating them from the enemy’s lines, the men in which had time only for one volley. The charge was perfectly successful, but there were, as I have said, no supports. The assault was evidently ordered, not because there was any definite object to be gained, but because it was thought a good thing on the whole to attack. Hence, instead of fresh troops being marched in through this gap, and taking the enemy’s works in reverse to the right and left, the gallant, but disordered, division which had carried the works was quietly allowed to remain, exposed to an enfilading fire from their right, and to the ceaseless attempts of the enemy in their front to dislodge them. After some hours their ammunition gave out. Repeated efforts to obtain a fresh supply were made, but in vain. At length, about nine o’clock or later, the enemy, having received reenforcements in the shape of Gracie’s(1) Brigade from Bermuda

***

(1) Gracie’s Brigade was not one of the original four brigades of Bushrod Johnson’s Division, which were those of Wise, Walker, Johnson, and Rawson. (3 So. Hist. Soc. Roster, p. 121.) It was transferred to that division from the Army of the Tennessee. It consisted of the 43d Alabama, 63d Tennessee, and the Alabama Legion, consisting of four battalions. (McCabe’s letter to J. C. R. Unp. Rep. M. H. S. M. p. 211.) It numbered at least 1400 men. (See Beauregard’s letter to Wilcox, ante, p. 120.) The 63d Tennessee was originally in Johnson’s Brigade of Johnson’s Division. (See Roster, p. 120.)

***

Hundred, made a last and decisive attack, and the gallant First Division of the 9th Corps was driven out, suffering greatly in killed, wounded, and prisoners.

Let us see now what the Confederate writers have to say of this affair. McCabe says:(1) “At dusk the Confederate lines were pierced, and, the troops crowding together in disorder, irreparable disaster seemed imminent, when suddenly in the dim twilight a dark column was descried mounting swiftly from the ravine in rear, and Gracie’s gallant Alabamians, springing along the crest with fierce cries, leaped over the works, captured over 1500 prisoners, and drove the enemy pell-mell from the disputed point.”

To the same effect, Beauregard: “Just as Gracie’s Brigade was forming, about sundown, in a little ravine in rear of Johnson’s lines, the enemy broke through the latter’s right centre like an avalanche, carrying everything before them. I then thought the last hour of the Confederacy had arrived, but at that moment(2) the gallant Gracie, having completed his formation, gave the opportune order to ‘forward,’ and then ‘charge,'” etc.

This evidence is decisive as to the very great importance of the point carried by this division of the 9th Corps; and I find it difficult to speak with patience of the gross mismanagement by which such a splendid chance for victory was lost. Such an operation as this should, of course, have been a subject of careful preparation at headquarters; fresh troops should have been in readiness to be put in the moment the attack had proved successful; tidings of the result of the attack should have been anxiously awaited by the commanding general, and

***

(1) 2 So. Hist. Soc. 269.

(2) Here General Beauregard is in error. It was some hours later.

***

everything should have been in readiness to secure the results of a successful charge. Instead, we find absolute negligence on the part of every one. Not even ammunition could be procured,— to say nothing of reinforcements.(1)

With this ill-managed affair the operations of the 17th of June closed. The enemy had actually captured more prisoners than we had. We had, however, shown Beauregard that his line was too far out. Probably the possession by us of the Hare house hill really rendered his line untenable, though this is not certain. At any rate he had determined during the day, as he tells us, to retire to an inner line, and he effected this quietly and securely during the night. This was the line occupied by the enemy during the remainder of the siege.

But where, all this time, was General Lee?

After the battle of Cold Harbor on the 3d of June, which was fought on the north side of the Chickahominy, the two armies fronted each other until the 12th, when Grant commenced his movement to the James. On the same day, and doubtless before Lee knew of this movement of his adversary, Lee sent Early with the 1st Corps to the Shenandoah Valley. On the 13th he discovered that we were moving to the James, and at once sent Hoke’s Division back to Beauregard, who ordered him up immediately to Petersburg, where, as we know, he arrived on the night of the 15th. On the same day, the 15th, Lee crossed the Chickahominy with Longstreet’s Corps, under Anderson, and A. P. Hill’s Corps, his only remaining troops, and marched in the direction of the lower Chickahominy, reaching the neighborhood of Malvern Hill

***

(1) General Burnside indeed says in his report (80 W. R. 523), that a portion of Colonel Christ’s Brigade of the Third Division participated in this attack, and that General Crawford of the 5th Corps rendered very efficient service. But I cannot find any corroboration of these statements. Christ had lost severely in Wilcox’s attack of the forenoon. And after considerable investigation I find nothing in the nature of an assault was made by Crawford. His operations contributed certainly nothing to the relief of the First Division of the 9th Corps.

***

that afternoon. If he meant to dispute our passage of the Chickahominy, he was too late, as the 5th Corps, preceded by Wilson’s Cavalry, had seized Long Bridge on the 12th, and on the 13th were in possession of the Long Bridge Road, where it crosses White Oak Swamp, where they effectually braved all approach by General Lee. While Meade was executing so admirably the withdrawal of his army to the James and was crossing that river, Lee’s army was in the neighborhood of White Oak Swamp and Malvern Hill, intrenching. Finally, after two precious days, the 14th and 15th, spent here, Lee took the alarm, and on the 16th marched with all speed for Drury’s Bluff, where he had a pontoon bridge, which was his only means of getting across the river. “On the night of the 16th he camped within a half-mile of Drury’s Bluff. Then Beauregard informed him by telegraph that he had withdrawn (on the 16th) all of his troops from the Bermuda Hundred lines except the battalion of heavy artillery at Battery Dantzler. . . . On the morning of the 17th Lee moved with Pickett’s and Field’s Divisions of Longstreet’s Corps to reoccupy these lines, spending the day at the Clay house near these lines. He reoccupied them,” says Colonel Venable, who was on Lee’s staff, “late in the afternoon. On the morning of the 18th he rode into Petersburg at the head of our advance, Kershaw’s (McLaws’s) Division of Longstreet’s Corps, arriving before or about midday.”(1)

We have a vivid picture of the march of the rear guard of Lee’s army in Caldwell’s History of Gregg’s South Carolina Brigade. “On Friday afternoon, the 17th, our division was carried back from the line of breastworks, and marched towards James River. That night, about an hour or two after dark (about 9 or 10 p. M.), we bivouacked, and resumed the march at daylight the next morning (18th, about 4 A. M.). We went directly to Drury’s Bluff, and crossed the James on pontoons. Then the rate of motion was accelerated, and

***

(1) Letter to writer, Sept. 26,1878. Unpub. Record M. H. S. M., vol. i, p. 40.

***

we pressed down the main road to Petersburg. The day was burning hot, and water was so scarce that men fairly fought each other at every well we reached. Every effort was made to keep up the men; but the continuation of such speed, under such a sun, and in the clouds of dust that stifled us, was utterly out of the question to a majority of the division. Regiments melted down to the dimensions of companies, and many companies had hardly a single representative left. A brigade would stretch for miles. For a time the sound of artillery in the direction of Petersburg gave promise of battle before night, and a sense of duty drove numbers along who were well-nigh exhausted; but, after marching at this racing speed for seven or eight miles, we found ourselves no nearer the firing, and a great deal nearer fainting. Then crowds of the very best soldiers fell out. . . . The first body of the brigade which reached the railroad was put on a train of cars and sent to Petersburg. Some shell were thrown at them by the enemy, but they passed on harmless. The rest of the brigade had to march as they could. A number of them did not reach their comrades until late on the following day (the 19th).”

Lee in fact had been outgeneralled. It is true, the control of the river gave us an immense advantage. When the Army of the Potomac was at or near Charles City Court House, as it was on the 14th, with Wilson’s Cavalry supported by the 5th Corps keeping the Army of Northern Virginia off at arm’s length, as it were, when the 18th Corps was at White House on the Pamunkey, as it was as early as the night of the 12th, the position of General Lee was certainly a difficult one. Our transports could carry our army anywhere. Lee at any rate preferred to wait until Grant’s intentions had been developed, trusting to Beauregard and his brave men to hold Petersburg against whatever force might be sent against it. And he was not deceived in his reliance on his lieutenant and his troops. But he ran a tremendous risk, and, so far as

one can judge, he should have moved much sooner. Nothing but the fortune of war prevented the fall of Petersburg.

The mistakes into which General Lee’s biographers have fallen in describing these operations are very curious. Thus Mr. Edward Lee Childe, his nephew, says that “on the 15th, at night, Lee’s advanced guard reached Petersburg. . . . Scarce arrived, Lee lost not a moment in raising some earthworks to the south and east of the town, and in fortifying himself.”

But it is Mr. John Esten Cooke whose narrative is the most amusing, from the light and airy way in which, with entire ignorance of the facts, he describes the state of General Lee’s mind, and attributes to him with perfect assurance the execution of those movements which to Mr. Cooke’s military genius seemed most natural and proper. “When morning came,” he says, speaking of the morning of the 16th, “long lines were seen defiling into the breastworks, and the familiar battle-flags of the Army of Northern Virginia rose above the long line of bayonets, giving assurance that the possession of Petersburg would be obstinately disputed. General Lee had moved with his accustomed celerity, and, as usual, without that loss of time which results from doubt of an adversary’s intentions.(1) If General Grant retired without another battle on the Chickahominy, it was obvious to Lee that he must design one of two things; either to advance upon Richmond from the direction of Charles City, or attempt a campaign against the capital from the south of James River. Lee seems at once to have satisfied himself that the latter was the design. An inconsiderable force was sent to feel the enemy near the White Oak Swamp; he was encountered there in some force, but, satisfied that this was a feint to mislead him, General Lee proceeded to cross the James River above Drury’s Bluff, near ‘Wilton,’ and concentrate his army at Petersburg. On the 16th he was in face of his adversary there. General Grant had adopted the plan

***

(1) The italics are mine.

***

of campaign which Lee expected him to adopt.”(1) This is certainly very entertaining.

It will be remembered that Grant had sent two divisions of the 6th Corps to Bermuda Hundred. He had learned that Butler, having discovered on the 16th that the enemy’s troops guarding their lines at Bermuda Hundred had been withdrawn to Petersburg, had in consequence occupied their works, and moved a force upon the railroad between Petersburg and Richmond. These divisions were sent to reenforce Butler, who had with him already a considerable body of troops. Butler, however, made no use of them whatever, and offered no effectual resistance to the reoccupation of their lines by the enemy on the 17th. General Lee, therefore, in spite of Butler, and all his forces, encountered no opposition in transporting his army from Richmond to Petersburg by rail, along the front of our lines, and only two or three miles distant from them!

To return now to Petersburg.

General Meade had, as he tells us himself,(2) ordered an “assault of the whole line for daylight on the 18th; but, on advancing, it was found that the enemy during the night had retired to a line about a mile nearer the city. . . . Orders were immediately given to follow and develop his position, and, so soon as dispositions could be made, to assault. About noon an unsuccessful assault was made by Gibbon’s Division, 2d Corps. Martindale’s advance was successful, occupying the enemy’s skirmish line, and making some prisoners. Major-General Birney, temporarily commanding the 2d Corps, then organized a formidable column, and about four P. M. made an attack, but without success. Later in the day attacks were made by the 5th and 9th Corps with no better results. Being satisfied Lee’s army was before me, and nothing further to be gained by direct attacks, offensive operations ceased, and the work of intrenching a line commenced.”

***

(1) The italics are mine.

(2) 80 W. R. 168.

***

Thus far General Meade. He makes a very short story of it, and by no means a very satisfactory story. There is no attempt even to show that he had any plan at all. From anything that he says to the contrary, any general in the army who thought it well to attack that day did so, on his own responsibility and without any concert of action, and without having any particular object in his mind to be gained by his attack.

But General Meade has not done himself justice in this brief narrative. Coppee, who wrote in 1866, and knew most of our officers well, says: “Instead of an attack in line, points were to be chosen which might be attacked in column, the columns to be followed by the lines in rear as reserves. In front of the 2d Corps three brigades of Gibbon’s Division were organized into an attacking column. These devoted men moved gallantly up to the enemy’s lines near the City Point Railroad, but success was not possible. … At four in the afternoon General Birney . . . formed a new column of attack, consisting of Mott’s Division and regiments detached from the other divisions,” etc.

It must also be remembered that General Meade was confronted this 18th of June with two new facts; first, the entirely new line to which the enemy had retired, and which there had been no opportunity whatever to reconnoitre; and secondly, the presence in this line during the day of very large reinforcements. The enemy’s retrograde movement necessitated a sort of right wheel of our centre and left, pivoting upon the Hare house hill; Barlow’s Division of the 2d Corps, the 9th Corps, and finally the 5th Corps, being obliged to make this movement. From the first the troops were exposed to artillery fire. When they reached the great ridge which runs almost due south from the Hare house hill, and on which Fort Haskell, Fort Morton, and Fort Meikle were afterwards erected, they began to be exposed to musketry. When they descended this ridge and endeavored to storm the

heights opposite, crowned with formidable works and manned with Lee’s veterans, they were necessarily defeated.

I have found it difficult to disentangle satisfactorily the events of this day. But we can learn the main features of it. On the extreme right, as we find from General Meade’s report, Martindale picked up some skirmishers, and on our right centre the 2d Corps made two desperate but unsuccessful assaults.

General Burnside states(1) that his Third and Second Divisions, under Willcox and Potter, advanced about 4 A. M. from the lines in the open ground in front of the Shand house, through the woods, under a heavy fire of musketry and artillery, driving back the enemy’s skirmishers to the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad; that they found the enemy in considerable force at the railroad cut and in the adjacent ravines; and were partially successful in driving him from a portion of the cut; that later, at 3 P. M., they drove him out entirely and established their extreme advance within one hundred yards of the enemy’s main line beyond the railroad.

General Potter says that the point where the mine was subsequently built was about the centre, or left centre, of his advance.

The 5th Corps advanced in line, with its four divisions, — Crawford, Griffin, Cutler, Ayres, from right to left. Much was expected from the 5th Corps that day. It had not been engaged seriously for weeks, — in fact since it left Spottsylvania; it had escaped, by its fortunate position, the terrible slaughter of Cold Harbor. It must have numbered more than 20,000 men. Marching from its position of the 17th on the left of the 9th Corps, its right division (Crawford’s) passed over the lines where the dead of Johnson’s and Ledlie’s Divisions lay, so thickly piled on both sides of the rifle-pits which had been fought over the evening before that, as an officer writes me, “it was impossible to march without stepping

***

(1) 80 W. R. 523.

***

directly upon the dead bodies of the slain.” The troops were exposed, as were also the 9th Corps on their right, as we have seen, to a severe artillery fire in their advance, and to a stout resistance from the enemy’s skirmishers; and instead of pressing forward over the great ridge and, in connection with the 9th Corps, making the attack on the enemy’s main position at once, the 5th Corps was halted under cover of the ridge, and began to intrench. This was at six in the morning, two or three hours at least before Lee’s troops had arrived. At that early hour there was a good chance of success, had the 5th Corps been promptly hurried in — had its commander seen fit to obey his orders. But he preferred to rely upon his own judgment, and his judgment was opposed to an attack. General Meade’s dispositions were perfectly adequate to the occasion. His orders to attack at once were peremptory, and they ought to have been obeyed. The time required to advance to the enemy’s new line, which was only a mile from the 5th Corps headquarters, and to make the necessary arrangements for attacking it ought not to have been for veteran troops, led by experienced generals, more than two hours or thereabouts ; and the troops were started at four o’clock. McCabe puts the arrival of the first troops of Lee’s army, Kershaw’s Division, at half-past eight; Beauregard says seven or eight; Venable says it was before or about midday. There was probably time enough for our army to have been thrown against Beauregard’s exhausted troops. But General Warren saw fit to halt his corps. This deprived the 9th Corps of support on its left, and in consequence the attack at this portion of the line was postponed until repeated and peremptory orders from the Commanding General had forced the 5th Corps forward. So, at three o’clock in the afternoon, the two corps attacked; they attacked then the Army of Northern Virginia, and though they displayed great courage, they were successful only in pushing their line close up to the enemy’s works. “Crawford gained the position from which afterwards the mine gallery

was run,” but “the enemy’s main line,” says General Warren in a letter, “was nowhere penetrated.” Vain were the efforts of Griffin and Chamberlain and Potter and many other brave officers and men. The position was too strong to be taken. There was a melancholy loss of life, all the more melancholy because it had accomplished so little, and because, had the Commanding General’s orders been promptly and zealously obeyed, a great success might have been gained. Never did the troops behave better, according to all accounts. “No better fighting had been done during this war,” says General Burnside in his report,(1) “than by the divisions of Potter and Wilcox during this attack.” “Though their men,” says McCabe,(2) speaking of the Federal Army, “advanced with spirit, cheering and at the run, and their officers displayed an astonishing hardihood, several of them rushing up to within thirty yards of the advance works bearing the colors, yet the large columns, rent by the plunging fire of the light guns, and smitten with a tempest of bullets, recoiled in confusion, and finally fled, leaving their dead and dying on the field along their whole front.”

General Lee, as we have seen, rode into Petersburg at the head of the advance of the Confederate Army, Kershaw’s Division of Longstreet’s Corps. This division was put in position on the salient, where the mine was exploded on the 30th of July. Lee was immediately in rear of this division when the great attack of the afternoon was made. A young artillery officer was shot down standing by his side.(3) Field’s Division was placed at Rives’s Salient, on Kershaw’s right and where the Jerusalem Plank Road enters the works, and still further to the right A. P. Hill’s Corps was placed. Apparently neither Field nor Hill was engaged on the 18th. It

***

(1) 80 W. R. 523.

(2) 2 So. Hist. Soc. 271.

(3) Letter from C. S. Venable, Unp. Rep. M. H. S. M. p. 41. Beauregard (ante, p. 123) says he placed Kershaw’s Division à cheval of the Jerusalem Plank Road. I incline to think Colonel Venable is correct.

***

does not appear what the enemy’s loss was. It was probably not very large.

Thus ends my narrative. The attempts to take Petersburg by assault having failed, “the work of intrenching a line,” as General Meade says, “commenced.”

A brief recapitulation may not be out of place.

1. Hancock and Smith could perhaps have carried Petersburg at six o’clock on the morning of the 16th, after Barlow arrived, and before Bushrod Johnson arrived.

2. Had the attack by Potter’s Division on the Shand house redoubt and lines at daybreak of the 17th been properly supported, Petersburg might have been taken.

3. So, had the attack of Ledlie’s Division on the evening of the 17th been properly supported, Petersburg might have been taken.

4. At any time during these two days a large force could have been sent to turn the enemy’s lines by way of the Jerusalem Plank Road, and Petersburg would have fallen.

5. Lastly, if Warren had strictly obeyed his orders, and had marched with all speed and attacked the lines at six o’clock on the morning of the 18th, in conjunction with Burnside, Petersburg would have been taken.

I have taken up already perhaps too much of your time. But I cannot close without expressing certain clear and decided convictions. It is the opinion of many observers that the constant attacks, which were such a prominent feature in the campaign of 1864, did, to a certain appreciable extent, demoralize the troops. I remember General Meade once making some such remark to me. A very competent officer writes to me on this subject as follows: “The Army of the Potomac, although preserving its organization in a remarkable way, was a blunt tool when it reached Petersburg. The Wilderness, Spottsylvania, and especially Cold Harbor, had killed out the men who, in a charge, run ahead; and the remainder were discouraged by incessant fighting and toil, and

by want of success. . . . The army could still march and intrench and obey orders, and resist heavy attacks; but for assault it was no longer available. Despite all this, fierce and determined attacks were made by Birney and others on the Hare house, by Potter on the Shand house, and by Griffin on Cemetery Hill.”

I cannot tell how much truth there is in this view, except by examining what actually took place. I have, of course, no personal experiences to assist me. But looking solely at what was actually done, I cannot hesitate to express my judgment, that, when the Army of the Potomac got down to Petersburg, it had all the capacity to make assaults that any reasonable general could expect. It cannot be expected of any soldiers that they should drive as good soldiers as they are themselves from behind works, unless they largely outnumber them. Hancock’s Corps, it is true, failed in their attack on the evening of the 16th, but of his three divisions only two, those of Barlow and Birney, were seriously engaged, and they had the whole of one division (Hoke’s) and at least half of another (Johnson’s) opposed to them. And what shall we say of the attack of Potter’s Division at daybreak of the 17th, or of the attack of Ledlie’s Division that evening? Whose fault was it that these brilliant and well-planned assaults did not bring victory in their train? And who can doubt that if the determined courage, so well described by McCabe as displayed by our troops on the afternoon of the 18th, had been expended in the gray of the morning on the exhausted, though heroic, soldiers of Hoke and Johnson, we should have hoisted our flag on the works of Petersburg? No, the trouble was, as I have said before in the course of this paper, not with the troops, — the troops, officers and men, fought well enough, — but no amount of courage will secure success in direct assaults unless that courage is both skilfully directed and well supported. The truth is, that no adequate pains were taken to utilize this courage. The Army of the Potomac at Petersburg possessed,

in spite of its disappointments, failures, and severe losses, a temper and daring quite sufficient for its tasks. The blame of the failure to take Petersburg must rest with our generals, not with our army.

———-

NOTE

We are able, I think, to approximate quite accurately to the numbers of the enemy in and about Petersburg on the 15th, 16th, and 17th of June, 1864.

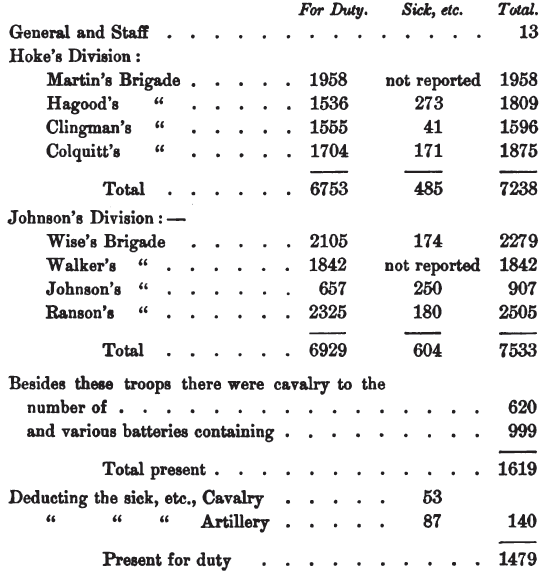

The very valuable “Confederate Roster” of Colonel C. C. Jones, 3 So. Hist. Soc., 120, 121 ad finem, gives General Beauregard’s force on May 21, 1864, as follows: —

Summary

On May 21, 1864, between which time and the 15th of June no action was fought at or near Bermuda Hundred, we find the following figures, stated by Confederate authority: —

This was exclusive of Gracie’s Brigade (in respect to which see note to p. 149, ante), numbering perhaps 1400 men.(3) This raises Beauregard’s total available force to 15,500 men. This is exclusive of men sick, and on detached service.

Colonel W. H. Taylor, in his Four Years with General Lee, publishes certain statistics taken from Original Papers in U. S. War

***

(1) 1932 in Dearing’s Cavalry, June 10. 69 W. R. 891.–Ed.

(2) See 68 W. R. 817, 890.–Ed.

(3) 2517, May 31. 69 W. R. 861.–Ed.

***

Department, and, on page 177, gives the strength of B. R. Johnson’s and Hoke’s Divisions on June 30, 1864, as follows: —

which, though a very heavy loss, is perhaps not to be wondered at, when we consider that these troops not only bore the brunt of our attack for three days, but also were constantly endeavoring by gallant and desperate assaults to recover from us any positions we had taken.

We must, therefore, hold that General Beauregard in his letter underestimates his force.

He gives the following figures [ante, pp. 116, 117]: —

The true number was, probably, as we have seen, about 2400 more.

McCabe, speaking in round numbers, says the works were manned by 10,000 brave men. This is an estimate too small by half,–I mean, that 15,000 is a fair estimate of the numbers of the Confederates.

***

(1) 2517, May 31. 69 W. R. 861.–Ed.

***

Source:

- Papers of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, Volume 5, pages 157-186 ↩