SOPO Editor’s Note: This debate originated over a year ago, when Jim Epperson (biography at http://www.civilwarcauses.org/bio.htm) and Brett Schulte (http://www.beyondthecrater.com) realized on a TOCWOC Blog post on an entirely different topic that they differed with regards to the Sheridan-Warren controversy at the April 1, 1865 Battle of Five Forks. Jim suggested a classic debate format to iron out our differences, and the rest is history, pun absolutely intended. 🙂 This post and one following shortly after, both published on April 1, 2015, one hundred and fifty years after the events described, contain our debate. I’ll let Jim take it away below with the details.

***

This is going to be an experiment, and we hope it does not blow up in our faces.

Over a year ago, in the comments following another blog post, it became apparent that Brett and Jim were on opposite sides of the Sheridan/Warren/Five Forks controversy. Jim happened to mention, casually, that a friend had once done a CWRT program on this in a debate format: He had taken one side (Warren’s) and recruited a friend to take the other side (Sheridan’s). Brett mused that this might be fun to do at The Siege of Petersburg Online, so here we are!

The formal question is the following:

Was Sheridan’s relief of Warren at Five Forks justified?

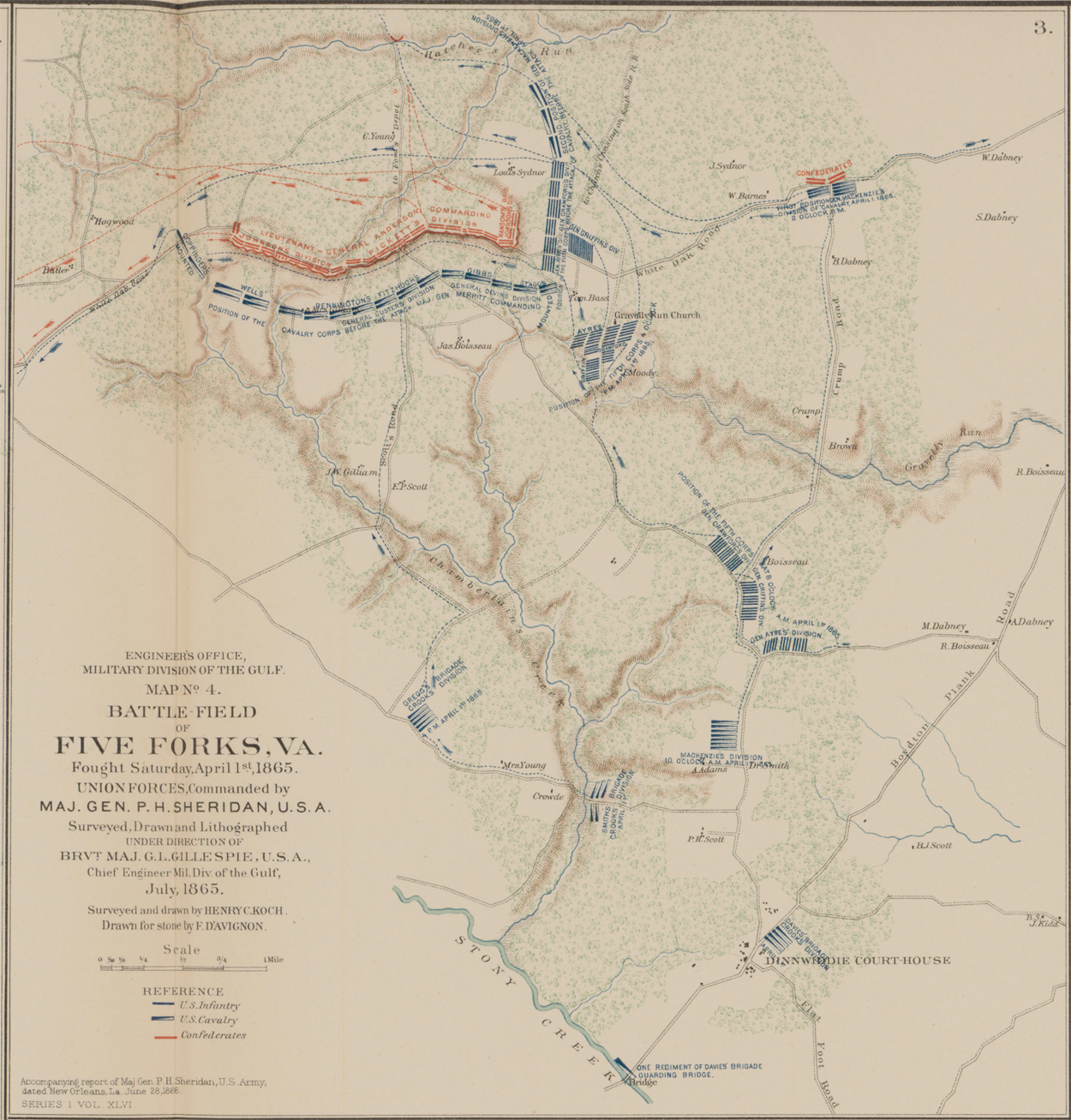

Since Jim is taking the affirmative side, he goes first, with a 1,000 word (approx.) essay. Brett will follow with an 800 word reply, and Jim will get a 200 word rebuttal. This initial post contains only this preamble plus Jim’s opening salvo. It is closed for comments in order to keep all the commentary in one place. The next post (which should go up at the same time tomorrow) will have Brett’s rejoinder as well as Jim’s rebuttal, and that is where everyone should feel free to chime in. Two or three maps are scattered somewhere in the mix. We have tried to footnote everything, in brackets at the appropriate place; e.g., [Babcock testimony, Warren Court of Inquiry (WC), vol. II, p. 901; see also Bearss and Calkins, p. 75.], which is Jim’s first footnote. The notes were not counted against the word totals, neither were the many repeated usages of rank (Major General Sheridan, Brigadier General Chamberlain, etc. The ranks were put in after the word counts were settled). Neither of us views this as a “competitive” debate, although both of us are sure we will carry the day 🙂 . Our purpose is to generate some interesting (and polite) discussion.

***

Jim’s Opening Argument

At approximately 11 o’clock in the morning, on April 1st, 1865, Lt. Col. Orville Babcock of Grant’s staff rode up to Sheridan near Dinwiddie Courthouse and gave a verbal message to the fiery Federal commander:1

“Tell General Sheridan that if, in his judgment, the Fifth Corps would do better under one of the division commanders, he is authorized to relieve General Warren …”

The text here is as recalled by Babcock during the Warren Court of Inquiry in October, 1880. The question before us is whether or not Warren’s conduct before or during the Battle of Five Forks justified Sheridan’s exercise of this discretionary authority. I think it did.

Warren made a series of errors on April 1st, which led to his relief by giving Sheridan—admittedly a hard man to work for—the impression that Warren was not the man to command the Corps at this crucial time. (We must remember that no one, on April 1st, 1865, knew that Lee’s army would be surrendering a week and a day later. They had to assume that there would be future battles, possibly serious ones, with the Confederates.) In near-chronological order, here are the mistakes I believe that Warren made:

- When Fifth Corps arrived at Dinwiddie Courthouse, Warren was not at the head of the column. Sheridan asked who was in command, and Chamberlain announced that he was in command of the leading two brigades. Told that Warren was at the rear of the column, Sheridan reacted angrily: “That is where I should expect him to be!” Sheridan was somewhat mollified by being told Warren was superintending the disengagement from the Confederates along White Oak Road. In any event, Warren should have made sure that a staff officer was present to speak for and represent the corps commander. This is basic military etiquette, and Warren’s failure to do so undoubtedly got him off on the wrong foot with Sheridan. In fact, it appears that Warren did not formally report to Sheridan until 11 a.m. on April 1st.2

- Warren had a bad habit, throughout his tenure as a corps commander, of substituting his own judgment for that of his superiors. (He had an equally bad habit of responding to orders with a treatise on why the orders were a bad idea.) He did it again in his move from White Oak Road to Dinwiddie Courthouse. His orders specified that only two brigades of Griffin’s division should go to Dinwiddie; the rest of the corps should follow Bartlett’s brigade of Griffin’s division, which had earlier moved generally west to the vicinity of the Boisseau farm. This would have put the bulk of Fifth Corps behind Pickett’s force in front of Dinwiddie, almost surely resulting in the wholesale capture of that force had it remained in place. However, Pickett realized his danger and pulled back before the Federals could take advantage of his exposed position. If the bulk of Fifth Corps had gone to Boisseau’s, then it would have taken less time to locate and develop Pickett’s new position, and the Battle of Five Forks might well have begun much earlier. If Pickett had not pulled back (something no one could anticipate), Warren’s decision to take the entire corps to Dinwiddie would have been seen as a major error.3

- In his report, Sheridan described Warren as giving “the impression that he wished the sun to go down before the dispositions for the attack could be completed.” In his Memoirs, Sheridan added that Warren said, “Bobby Lee is always getting people into trouble.” This is the only source for this assertion, and many authors have claimed that here Sheridan was simply lying about Warren. This is possible, but I insist that it is also possible that Sheridan was presenting—no doubt in a way to damage Warren as much as possible—what really happened. Interestingly, in his testimony at the Warren Court of Inquiry, Chamberlain does not deny that Warren might have acted diffidently, but attempts to explain it away as a peculiarity of Warren when intensely focused: “General Warren … instead of showing excitement, shows an intense concentration … those who do not know him might take it to be apathy.” Bearss and Calkins suggest that this is the conflict between the extrovert and fiery Sheridan, and the introvert and analytical Warren.4

- The particular errors which prompted Sheridan to relieve Warren came during the battle. At the outset of the battle, Fifth Corps was further east than was thought to be the case, so when they advanced they missed their intended target, the “knuckle” in Pickett’s line. Upon taking fire from the Confederates in the knuckle, Ayres’ division (2/Fifth) and then Griffin’s division (1/Fifth) began to wheel left to confront and attack the enemy5, but this happened too slowly to suit Sheridan, whose cavalry were taking more casualties by skirmishing along Pickett’s front. Crawford’s division (3/Fifth) did not conform to the shift by the other two divisions. In an effort to redirect Crawford into the attack, Warren rode off to find Crawford (after sending several staff officers to do this, to no avail). Thus, when Sheridan tried to communicate with Warren, the Fifth Corps commander could not be found. Ironically, Crawford’s looping path brought his troops onto the Ford Road deep in the Confederate rear, cutting off their retreat. (However, if Crawford had conformed to the rest of the corps, the knuckle would probably have been overwhelmed sooner and with fewer Federal casualties, and Crawford would have reached Ford Road sooner than he actually did, probably with the same effect.)6

Do these errors justify Warren’s removal from command? That is a fair question. The Federals had just won a resounding victory—some 3,200 prisoners had been taken—so why relieve the commander of Fifth Corps? The answer is simple, if a bit cruel: Sheridan had been given the discretionary authority to do so, and he chose to exercise that authority. All he knew was that the Fifth Corps commander had not acted energetically to prepare for the battle, had not attacked when he wanted him to, where he wanted him to, and when he had tried to find the corps commander to prod him into action during the fighting, Warren was not to be found. Sheridan apparently believed that “the Fifth Corps would do better under one of the division commanders,” and that is frankly all the justification he needed. Cruel? Perhaps. Mean-spirited? Very likely. But I like to quote Bruce Catton on this point7:

“Sheridan had been cruel and unjust—and if that cruel and unjust insistence on driving, aggressive promptness had been the rule in this army from the beginning, the war probably would have been won two years earlier…”

***

Stay tuned for part two, containing Brett’s response and Jim’s final rebuttal, coming soon…

- DEBATE: Was Sheridan Justified in Relieving Warren at Five Forks, Part 1

- DEBATE: Was Sheridan Justified in Relieving Warren at Five Forks, Part 2

Notes:

- Babcock testimony, Warren Court of Inquiry (WC), vol. II, p. 901; see also Bearss and Calkins, p. 75. ↩

- Chamberlain, The Passing of the Armies, p. 104; Chamberlain testimony, WC, vol. I, p. 234; Warren says he decided to report to Sheridan at 11 a.m.; Warren testimony, WC, vol. 1, p. 741 Sheridan, WC, vol. I, p. 55. ↩

- OR, ser. 1, vol. XLVI, part 3, p. 367: “Send Griffin promptly, as ordered by the Boydton plank road, but move the balance of your command by the road Bartlett is on and strike the enemy in rear, who is between him and Dinwiddie.” Examples of his “treatises” come during Spottsylvania (Matter, If it Takes All Summer, p.109, original letter in New York State Library) and Peebles Farm (Sommers, Richmond Redeemed, pp. 242-243, OR ser. 1, vol. XLII, part 3, pp. 19-20). Sommers concludes that Warren “feared responsibility … for grand tactics.” ↩

- OR, ser. 1, vol. XLVI, pt. 1, p. 831 (Warren’s report); Chamberlain, WC, vol. 1, p.236; Bearss and Calkins, The Battle of Five Forks, p. 90; Sheridan’s Memoirs, p. 326. ↩

- Griffin’s move was actually more complicated. He was behind Crawford, and as Ayres veered left and Crawford veered right, a gap was created, and Griffin first moved into that gap, then turned left to conform to Ayres. ↩

- Bearss and Calkins (pp. 109-110) suggest that Sheridan relieved Warren because he was not present to rally one of Ayres’ brigades when it faltered a bit. ↩

- Bruce Catton, A Stillness at Appomattox, p. 358. ↩

Recent Comments